Long ago, I worked at a school whose teachers formed an enthusiastic crime fiction group and the Head of Chemistry recommended Post Mortem by the relatively unknown Patricia Cornwell: I stayed up until 2.30 in the morning to finish it and spent the rest of the night checking that the doors and windows were locked.

Ever since, I’ve loved a good autopsy, whether in print or on screen, and passed on that love to my family. The TV series Bones based on Kathy Reichs’ books, was so adored in our house that my offspring, at the age of five, announced her intention of studying Anthropology at Uni. She has never wavered and now it comes in useful, as the following WhatsApp conversation illustrates.

Me: I have a body indoors been dead around three hours. Would there be flies yet? October, but not too cold

Offspring: probably they get going on a dead body pretty quickly. As long as there are flies in the vicinity ofc

Me: Bound to be. I refuse to believe Ancient Rome didn’t have flies

Offspring: oh defo they were nastyyyyy

Me: ok shall put in yucky sentence about fly landing on dead body

Isn’t it good to be able to talk to your kids?

Once I started writing historical fiction set in the world of first century Rome, I had a problem, because so much of what I loved about crime fiction seemed to be forbidden. Our word “forensic” comes from the Latin forum, the central square of every Roman town and the place where trials would have been held, but “forensic” has expanded in meaning. I knew that I would be unable to include the exciting tools of the modern detective, fingerprints, facial recognition software, DNA. My detective would not write monographs on types of cigar ash nor would a Crown Prosecution Service run the prosecution. There was not even a police force: Rome’s city brigade known as the Vigiles was set up primarily to put out fires, although Lyndsey Davies has ingeniously co-opted them in her Falco series, saying of her book Time to Depart, “…this is a groundbreaking Fire Brigade Procedural: still scope to dwell on the squaddies in the station house complaining about the poor pay, the dangerous work, the abuse from the public, the disinterest of their superiors”.

There would have been no crime scene techs and there was no guarantee that bodies would be seen by a medical professional. Doctors were expensive, and who was going to pay a doctor when the dearly departed was clearly dead? We do know of one autopsy (though whether it merits being called that is debateable), the examination of Julius Caesar’s body which was recorded by the biographer Suetonius – “According to the opinion of the doctor Antistius, amongst so many wounds, only one was found to be fatal, the second one, which was made to the breast.” Nobody would have dreamed at that time of cutting open a corpse: given the circumstances of Caesar’s assassination there would have been little need for the body to be opened, even if it had been socially acceptable.

The way to go, I thought, was to turn it all around – what did the Romans do well when it came to crime? They did love a good trial so we have speeches and accounts of trials with some juicy information. Scandalous accusations, political intrigue, magnificent oratory can all be turned to use in a crime novel, as Steven Saylor has shown in his Roma sub rosa series. The first of Saylor’s novels, Roman Blood was based on the real case of the murder of Roscius of America. It’s a terrific novel, and Saylor’s use of the defence speech is so good that when the speech was on the Latin A level syllabus, I made my students read Roman Blood. This speech is one of the earliest we have by Cicero, the lawyer/politician who features in Robert Harris’ magnificent Imperium trilogy and was memorably dramatized in a BBC Timewatch episode Murder in Rome.

From teaching Cicero for twenty-five years, I knew that when a case came to trial Roman judges were quite keen on witnesses and liked a good bit of evidence though I was interested to discover a passage in which Cicero warns fellow lawyers against the use of circumstantial evidence, using a hypothetical example – a murder is committed and a bloody sword is found in a man’s possession. The blood, however, came from someone else using the sword to commit the murder, then putting the sword back in its sheath uncleaned.

It was also expected that the lawyers would put forward arguments concerning character and “what was likely”. Unheard of today, of course, but especially useful for a fiction writer because we are also allowed to work with what might be reasonably assumed – in my case, that there would be some analytical expertise available to fictional detectives working in the ancient world. In Egypt, the city of Alexandria was a hub of learning that trained many of the greatest doctors and scientists of the ancient world. In the third century BCE, there had even been a few decades when dissection of human bodies was allowed and huge leaps in understanding were made before the practice was outlawed once more. This filtered down through the centuries, so I reasoned that doctors might well be knowledgeable about human anatomy, especially those in the military, whose experience might well include blood clotting, wounds and time of death. The American writer, John Maddox Roberts wrote a much-admired series of mysteries, SPQR, in which he introduced the doctor Asklepiodes who works in a gladiatorial school and therefore has a superb knowledge of wounds and the weapons likely to have caused them.

The sources also show there was a great deal of knowledge about poisons: famous Vesuvian victim Pliny the Elder is a treasure trove of dubious detail, my favourite being that hedgehogs can poison themselves with their own urine, a lesson for us all. The slightly more reliable Dioscurides produced his great work on the pharmacological properties of plants De materia medica in the first century CE. This came in useful when I was writing my novel Poetic Justice: I needed my hero to be given a hallucinogenic dose of something and Dioscurides recommended belladonna.

Like every writer of historical fiction, I end with Hilary Mantel as my guide. The past may limit my detective’s range of tools and skills but there will be opportunities: “We should seek out inconsistencies and gaps and see if we can make creative use of them.” There are many gaps in my ancient sources, many inconsistencies – but there is also an intriguing treasury of material left behind by people who rightly thought that what they had to say would be interesting to later ages.

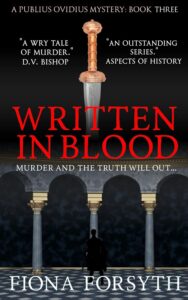

Written in Blood

Fiona Forsyth